The Gunnison Valley is famous for the network of trails that wind their way through the surrounding mountains. But how do all of those trails impact the wildlife? Western Colorado University graduate Chloe Beaupré wants to find out.

Beaupré recently published research showing that trail use impacts wildlife species differently, with some more affected than others.

The study, published in the journal Ecosphere and titled Recreational trail traffic counts and trail proximity as a driver of ungulate landscape utilization, offers new insights into how elk and mule deer respond to trail use and human presence.

Beaupré and her collaborators – including fellow Western graduate student Alissa Bevan, Western Provost Dr. Jessica Young, and Colorado Parks and Wildlife biologist Kevin Blecha – deployed more than 100 motion-activated cameras in 59 pairs throughout the Upper Gunnison Basin. One camera faced a trail, and another was positioned 100 to 1,800 meters away from the same trail.

“Most studies target trails or try to measure recreation and wildlife in the same location,” Beaupré, who was the first student in Western’s Clark School of Environment and Sustainability to earn both a Master of Environmental Management and a Master of Science in Ecology, said. “We were interested in how animals behave on and off-trail in response to human activity happening on a trail, and in understanding how far those effects extend.”

Inspired by a recent planning effort focused on recreation in the Gunnison Basin, the researchers studied a sample of everything from unmaintained dirt roads to singletrack trails only accessible to pedestrians and equestrians.

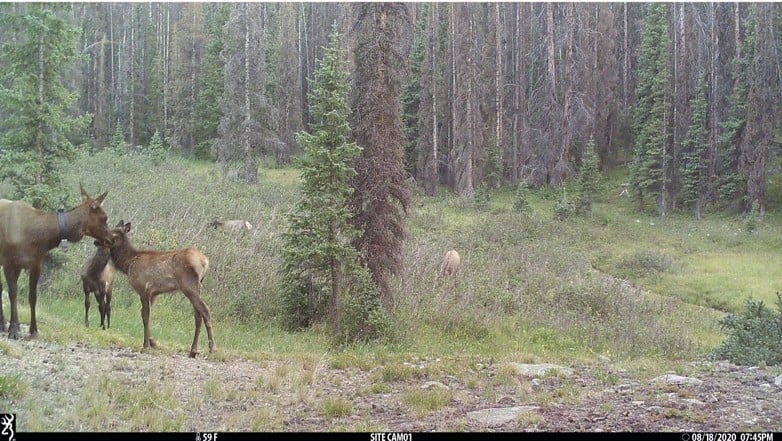

During the 2020 research period, which stretched 160 days from the end of June to early December, the team recorded more than 130,000 photos of humans using the trails (approx. 71,000 motorized, 59,000 non-motorized) along with roughly 22,000 mule deer photos and 10,000 elk photos.

“I was very surprised by the number of recreators that are out there!” Beaupré said. “At some cameras, it was almost nonstop traffic throughout the day and sometimes into the night and early morning.”

When the photos were analyzed, the researchers could clearly see that elk and mule deer respond to recreation in dramatically different ways.

Elk were much more likely to steer clear of the trails, and the more traffic on a trail, the less likely elk were to be nearby. The research suggests a “critical distance threshold” of 655 meters from trails, at which point elk activity decreased significantly.

Conversely, mule deer were much more likely to be present near high-traffic trails. Unlike with elk, the research couldn’t identify a distance at which deer became uncomfortable with the human presence, according to the paper, “as the distance-to-trail variable had no significant effect.” According to Beaupré, that may reflect a regionally specific “human shield effect,” where deer are drawn to areas with more people because predators tend to avoid them.

The research was made possible through funding from the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, and the Margie and John Haley Fund. The findings could help shape trail planning and recreational management throughout the western U.S.

“For people who enjoy hiking and biking, it’s important to be cognizant that recreation does have an effect on wildlife. I know most of us love a wildlife sighting in the woods, but to ensure these moments remain possible in the future, we need to be thoughtful about how and where we recreate,” Beaupré said. “Respecting seasonal closures, sticking to designated trails, and leaving some areas as true wildlife refuges can go a long way toward supporting healthy habitats.”

As outdoor recreation continues to increase across the West, the need for thoughtful, data-driven land management is more urgent than ever.

“I’d encourage managers to focus recreation traffic along certain trails rather than promoting sprawl across the landscape, and to plan any new trails within the 600-meter footprint that is already being disturbed,” Beaupré said. “Certain trails may even need to be decommissioned if they extend that footprint. This isn’t about choosing people or animals, it’s about finding smart ways to share the land.”

Lead the Change You Want to See

Join a community of bold thinkers and passionate problem-solvers. In the Master’s in Environmental Management program, you’ll dive into real-world research, work side-by-side with faculty and peers, and develop the skills to create lasting environmental impact.