With just over a minute left in the third quarter of the Western Colorado University Mountaineer’s biggest football game of the season, senior wide receiver Sage Yazzie took his place on the line of scrimmage and waited for the snap.

With it came a flurry of action as the defense swarmed the quarterback. Three steps off the line, Yazzie cut hard across the middle. Through a forest of defensemen, the quarterback hit him on the run at the 30-yard line. Yazzie pulled the ball in close and rolled across the turf, a defender clinging to his back. With the catch, he’d dashed any hope the School of Mines had for a comeback. But something wasn’t right. When he got up and stepped on his left foot, he hesitated, then took another step, a pronounced limp in his stride. His hand came up, and he called for a substitute.

While Western would go on to win against Mines, the game could have been over for Sage. With a high ankle sprain, it was possible that he wouldn’t make it back for what remained of the 2024-25 season. It was one of those moments when it became clear that, for Sage, one part of life was about over, but another was just beginning.

Finding Strength in Football

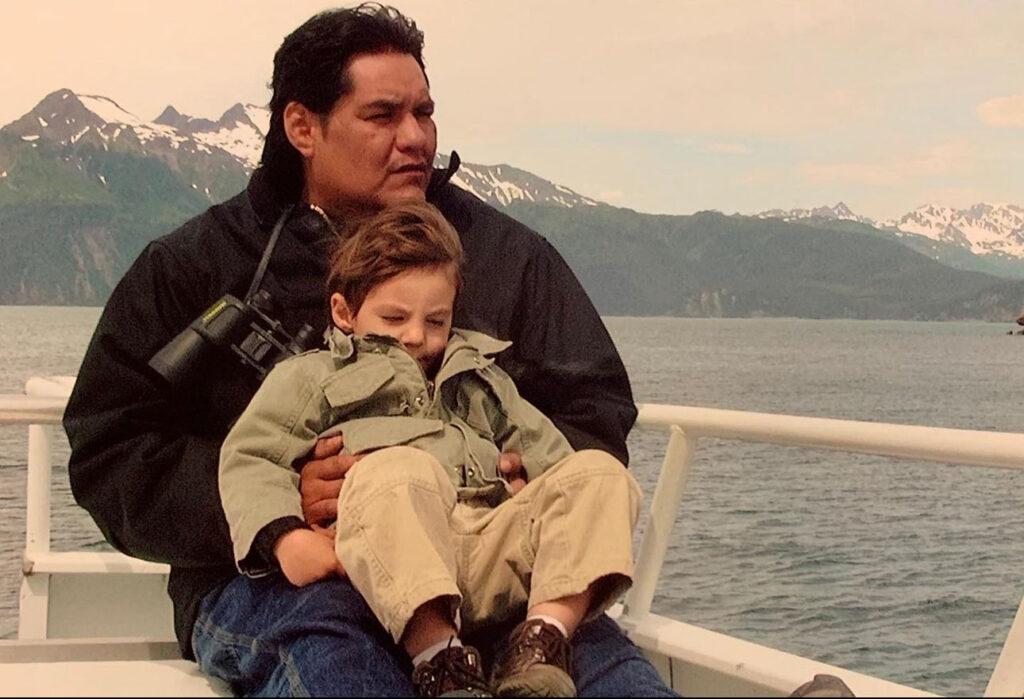

Sports, and football in particular, have been a big part of Sage’s life for as long as he can remember. It was a pastime that had taken on a special significance for what it provided his father and four uncles, who all played basketball and football growing up in Ganado, AZ, on the Navajo Nation. “It’s just been deeply rooted into our family,” he said. “I started at a young age, and it just kind of grew from there.”

As a kid, he spent every summer on the Reservation, where sports were part of the fabric of life. As he made his way through high school in a Denver suburb, playing football, basketball, and baseball for the Longmont Trojans, he grew into a 6’2” 200-pound frame that was made for the game.

In his senior year, he was projected to be an all-conference pick in football. He had real Division I potential and was thinking about the University of San Diego. But just as the future started coming into focus, everything changed. In the fourth week of his last high school season, his father fell ill and died, leaving him without the inspiration that had always been there, somewhere behind every catch.

The day of his father’s funeral was the first time he had ever missed a practice or a game. “After he passed away, especially in the middle of football season, football just became the activity that showed him how hard I was working, even though he wasn’t here anymore,” he said. “That gave me a lot of pride and motivation, with him always watching over me.” Still in mourning, after being shaken to his roots, he returned to the field strong and delivered standout performances. Once again, the future looked bright.

Connecting with Tradition

Sage knows how lucky he is to be able to go to college to play football and represent a Native population that isn’t well represented in sports or anywhere in American culture. On the Reservation, he knows of kids who have had to balance school and work just to keep their families afloat. In his own life, the contrast was plain to see. His mother and her sister had college degrees; their father was a professor at Oklahoma State University. Sage’s father had come from much different circumstances.

“My dad was 100% Navajo, and I definitely grew up around my Native side more,” he said. “That’s what I value from a traditional standpoint.” But those relatives lived a hard life. He had seen so many of his family members die before they were old, including his own father. Others had to make a Herculean effort to have a comfortable life. One uncle drove five hours to Phoenix every week for work because there was none on the Reservation. “When you go down there, it feels like a whole different country, just having had both experiences,” he said. “I would go from a very comfortable living situation on my mom’s side. And then going back to the Reservation … it’s just a lot harder lifestyle.”

“My dad was 100% Navajo, and I definitely grew up around my Native side more,” he said. “That’s what I value from a traditional standpoint.” But those relatives lived a hard life. He had seen so many of his family members die before they were old, including his own father. Others had to make a Herculean effort to have a comfortable life. One uncle drove five hours to Phoenix every week for work because there was none on the Reservation. “When you go down there, it feels like a whole different country, just having had both experiences,” he said. “I would go from a very comfortable living situation on my mom’s side. And then going back to the Reservation … it’s just a lot harder lifestyle.”

The summers were hot on the arid edge of the Colorado Plateau, without much reprieve from a cool breeze or a shade tree. The winters were cold and snowy, with wood-burning stoves the only source of heat. “I loved going back there as a kid,” he said. “It was like we lived so secluded from everybody and it’s quiet. You’re just kind of living off the land.” He chopped wood and lived simply, letting the first-world problems he dealt with back home fade away. As confining as the Reservation was in some respects, it was also freeing and immense, with unfathomably huge spaces, an endless blue sky, and a deep silence match. As hard as that country was, he saw the beauty in it, too. “I had a pretty rough childhood growing up with my family situation. I saw counselors, but therapy wasn’t really for me,” he said. “I just always used the outdoors as my escape and my therapy.”

The Rise of Native Nature

As his search for the right college narrowed, he was split between San Diego and Western. San Diego is a private college that doesn’t offer athletic scholarships. And Western was surrounded by mountains and the open space he had been drawn to as a boy. Here, he could chase his passions for snowboarding, backpacking, and fly fishing year-round. “I had taken more visits to San Diego than Western. But I was here for 24 hours before I committed to play here. And I couldn’t be more happy. I just immediately felt at home,” he said. “It was the perfect fit for me. Everyone was so welcoming and genuine. I could just tell how this place has people with the same kind of personality, just being themselves. That really made me feel at home because I didn’t feel at home at all back home.”

After settling in at Western, where the football team had a big-family feel, he looked over the course catalog and settled on a Psychology major with a minor in Recreation and Outdoor Education. He’d seen how wild places and open spaces had helped him on his own journey and saw his experience in life and in the outdoors as an opportunity to help others. Not long after, he discovered that the photos and videos he’d been taking on his phone for years had become more than just digital memories. They’d become an art form he was increasingly passionate about sharing with others. Finally, with his tools in order, it was time to start giving back.

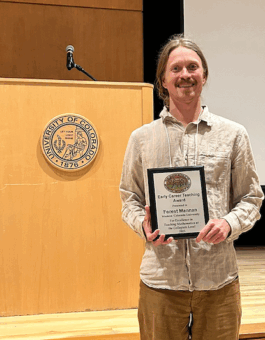

Two years ago, Sage got a coveted internship in the marketing division of Gore-Tex, the famed textile brand, which put him in contact with oakpool, Gore-Tex’s third-party marketing team. “They liked my work,” he said, and as soon as his first internship ended, oakpool asked him if he’d like to start a second internship with them. Soon, he was a contractor working with brands like Gore-Tex, Boulder Boatworks, Bear & Burton’s, Trout Mount, and The American Fly Fishing Museum.

It was a relationship that served him well. It motivated him to start his own photography and videography company, Native Nature, LLC, which offers marketing services through oakpool. As a student-athlete, he’s been able to continue working for the company as a contract employee, keeping a foot in the door of a growing industry and working on a storytelling craft that he hopes to build into a career of helping others find peace in the outdoors. “I still want to showcase the mental health part of it in everything I work on,” he said. Next summer, he hopes to start working on a project that will tell his own story of struggle and triumph.

“I think my dad would be most proud of my sense of purpose,” Sage said. “He never really was a hard ass about me being good at football or getting recruited to play in college or anything like that. He just always wanted me to be happy. That’s all. And I’m genuinely happy with where I stand and what I’ve done.”

Want to be a part of the story?

Be part of a community that’s curious about the world and driven to make a difference. In the Behavioral & Social Sciences Department, you’ll work alongside faculty and peers to explore human behavior, challenge assumptions, and create real change.