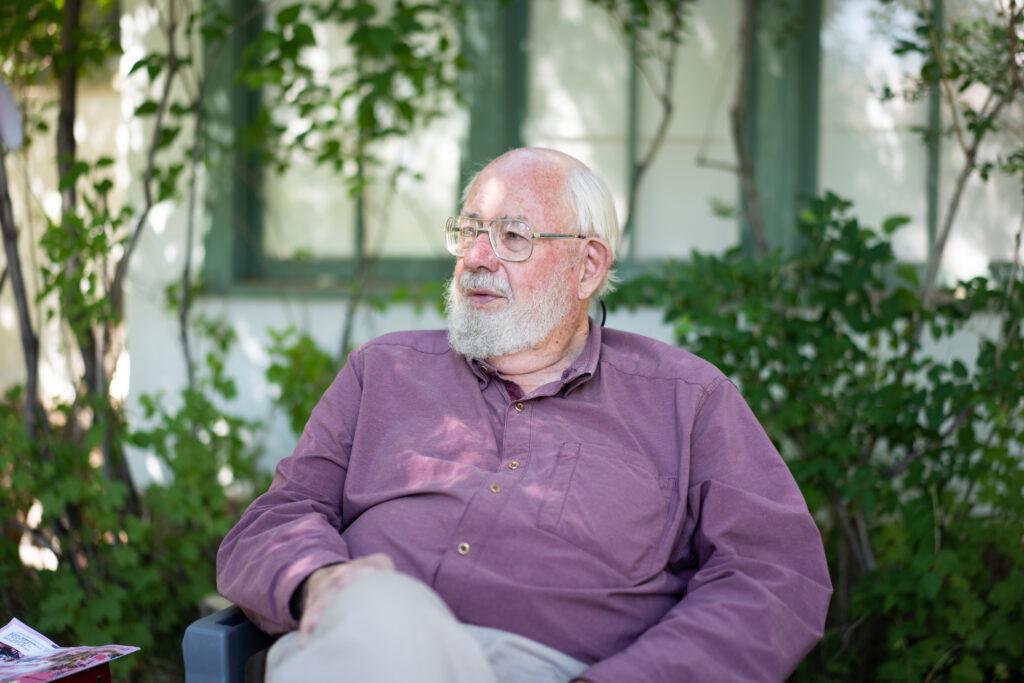

By most standards, Butch Clark is a big guy. Although he has an exceedingly gentle demeanor, with a frame well over six feet tall, broad shoulders, and a powerful, deep voice, he’s someone who rarely goes unnoticed in a room. But as big as he is, his physical presence pales in comparison to the scale of his ideas.

For years he spent his Tuesday mornings attending Gunnison County Commissioner meetings waiting for the chance to weigh in on the topic of the day. Often, the commissioners would pause at the end of their discussions to ask him what he thought. And more than once, he tried to convince them that a bold course of action was the right one. Although his ideas were always logical and well-researched, they often went no further than a flurry of head nodding and note-taking. His ideas, it turned out, were just too big.

Years before he attended those meetings as a member of the public, he campaigned to be a County Commissioner, hoping he could effect change from the head of the table. But back then, the county’s voters weren’t interested in progressive ideas or a county commissioner who had them. His ideas are the kind that just might change the world — or save it. What scared people most is that while he has a global perspective that comes from a well-traveled upbringing and an education that crossed the country and spanned the Atlantic, he knows that if the world is going to change, it has to start right here at home.

The Beginnings

Home wasn’t always in the Gunnison Valley. Butch was raised in Cincinnati, with vacations spent on a family farm in Libertyville, Illinois, 40 miles north of Chicago. But for generations, both sides of his family had maintained a steady westward gaze. After graduating from Yale University in 1884, his father’s father moved out to what is today Casper, Wyoming, but back then it was just an outpost, to work as a lawyer and clerk for a judge. His maternal grandfather, who owned an insurance company in Chicago, traveled through the same territory in 1892 in search of cattle for his farm in Libertyville.

His father also loved the West, where he traveled and lived for a time, and would one day start work on a book about the Oregon Trail. So it made sense that Butch would head to Wyoming every summer during his college years to work on a ranch and form the foundation of what would become a lifelong love of the Rocky Mountain West. It’s where he met his wife, Judy, who was one of the finest equestrians in the south of England when she came to the U.S. to travel and ride. The West is also where he went after his Vietnam-era service in the Air Force was over, and he found himself just a few classes short of a master’s degree.

The Way to Gunnison

“We were looking around for a place I might want to finish my master’s. My father was taking some European friends along the Oregon Trail and sort of looped down this way because he hadn’t been down here before. He passed through Gunnison and said, ‘Why don’t you finish your master’s at Western.’” That was the start of a half-century spent in Gunnison.

Coldharbour’s Birth

In March of 1970, Butch and Judy moved into a house not far from campus and settled in for the long haul. They loved the landscape and the community. Butch finished his master’s degree in economics, and the couple made some of their closest friends. They had visions of starting a dude ranch of their own and purchased more than 900 acres with some cabins at the top of Lost Canyon to get started. But when reality rendered their plan unfeasible, and Judy’s parent’s health started to decline, Butch enrolled in a Ph.D. program in England where he would study the impacts that boom and bust industries had on communities, returning to Gunnison each summer. One summer, they bought a little over 300 acres east of town on Tomichi Creek, where they imagined growing vegetables and providing a place for students to do research. He called the property Coldharbour. “I wanted to protect it,” he said. “One of the things I did pretty much right away was establish it as a federal wetland reserve. It needed that protection. Things could be messed up and scraped around out there. Eventually, it went over to Western.”

His experience on his grandfather’s farm as a boy and the ranch in Wyoming as a young man showed him the power of landscapes and their ability to change people, but also how they could be changed in the march of progress. He saw how industry, particularly mining, could move in and then move on, leaving holes in the ground and holes in the communities that had sprung up to support them. As he fell deeper in love with the Gunnison Valley, he watched as Crested Butte was repeatedly able to stave off a molybdenum mine on Mt. Emmons. It was that cumulative experience of seeing how fragile such a rugged place could be that left a lasting impression.

Big Ideas and Change

Changes need to start at home, and ideas need to take hold and start with the self. Big ideas, Butch knew, were best had about the one person they weren’t too big for: himself. Through active involvement in local and regional organizations, Butch made a deliberate effort to safeguard the future of the place he’d come to call home. Butch started his campaign of big idea implementation a decade before he turned Coldharbour into the Coldharbour Institute and made it available to the Clark School of Environment and Sustainability as “a learning laboratory for regenerative living practices.” He started his philanthropic campaign with a gift of his land in Lost Canyon for the benefit of affordable housing projects in The Valley. That arrangement, which gave ownership of the land to the U.S. Forest Service in exchange for a sizeable donation to be made to the Gunnison Valley Housing Foundation, was an effort to protect the community against the kind of mess he’d seen industry make in mining towns around the west. The gift of Coldharbour was his second salvo in an effort to protect the future.

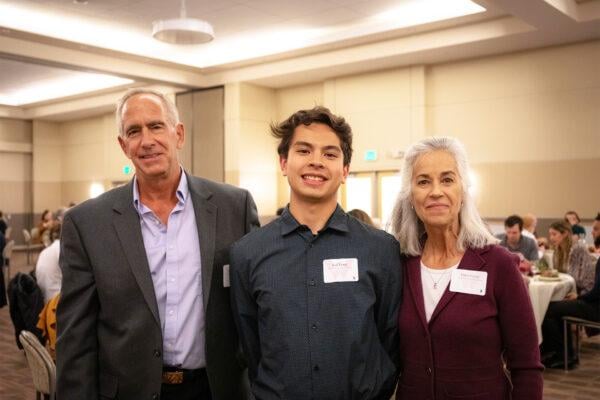

“We need to do a lot of thinking now about the environment,” Butch says, looking back on the gifts he and his father have given to Western over the years, which ultimately led to the School of Environment and Sustainability taking the Clark name. His father gave $1,000 in 1999 and two years later gave another $100,000 to help the nascent Environment and Sustainability program at Western. Followed suit with his own donations of land and cash, which added up to about $4.5 million, with $2 million of it serving as an endowment that provides an income stream that helps support the Clark School’s fellowships and faculty.

On a rainy Tuesday this spring, as he walked around the Coldharbour property, it was clear he wanted to talk about anything but his gift to the University. He was happy to talk about big ideas, to relive the last half-century he’d spent with Judy in Gunnison. He wanted to talk about his plans to remodel his home so it would be more comfortable for visiting speakers, Ph. D.s, and guests who come to Gunnison to contribute in their own way to the Clark School and the University he loves. “They were kind to me, the professors were,” he says of Western. During our visit, he wanted to talk about the impact his giving could have or the work that still needs to be done, but he didn’t want to talk about money. He knows he is fortunate to have had generations of family members before him who taught him to love institutions of learning and the land and, ultimately, provided the means for him to pursue his passion for it. That support has allowed him to give freely of his knowledge, his time, and his resources without asking for much in return. He really wants to talk about his hope that his gift is an investment that one day will pay dividends.